The Role of the Media in Russia’s Economic Development

(Otechestvenniye Zapiski, A journal of socially significant issues, Moscow, 2003 No. 4. Original text published in Russian. Click here to see)

By William Dunkerley

Russia’s media could have been providing a significant boost to economic growth. But they haven’t. The media have not taken up this role — one which they play typically in economically successful countries.

That is not all, however. Russia’s media have not merely abdicated that role. They themselves have actually served as a negative economic force, impeding growth.

That may seem like a stinging indictment of the media. In their defense, however, I should point out that none of this has been the media’s fault.

Who is to blame? How have the media obstructed economic growth? What role can they really play in boosting the economy? And, how can things be changed so that the media will play a constructive economic role? I’ll try to provide answers to these important questions.

The Media as an Economic Sector

The media’s most obvious economic role is as a sector of the economy. Media companies employ people. They buy and sell products and services. They even pay taxes.

However, the media do not constitute a large sector of any country’s economy. In the United States the media industry represents just 5.7 percent of the gross domestic product, according to media merchant bank, Veronis Suhler Stevenson.

How does that compare to other countries? Lamentably, relative data on the size of countries’ media sectors is not readily available. It is, for advertising expenditures, though. U.S., advertising expenditures total 1.37 percent of GDP. In Russia, it is 0.60 percent. These figures, and the ones presented below, were provided by ZenithOptimedia.

Here is a table that compares Russia with several Western countries:

Advertising as Country a percent of GDP

Greece = 1.47 percent

United States = 1.37

Switzerland = 1.00

United

Kingdom = 0.98

Germany = 0.85

Russia = 0.60

Clearly, Russia’s advertising expenditures pale in comparison. Interestingly, the same is true when Russia is compared with other post-communist countries:

Advertising as a Country percent of GDP

Hungary = 1.98 percent

Czech Republic = 1.43

Poland = 1.38

Bulgaria

= 0.92

Estonia = 0.75

Latvia = 0.72

Russia = 0.60

Lithuania

= 0.44

Romania = 0.42

Indeed, it seems that advertising expenditures of the group of countries with emerging market economies, actually average higher than many of Western Europe’s most developed economies! Media as an Indirect Influence

Recently, the World Bank published a book entitled, The Right to Tell — The Role of Mass Media in Economic Development. It deals not with the direct impact of the media upon a country’s economy, but with the indirect influence it exerts, i.e., by giving citizens the information they need to exercise vigilance over government.

Speaking to the press, the book’s editor, Roumeen Islam said, “The key message is that an independent media can boost economic development by promoting good governance and empowering citizens. It can make economies function better.” In the book, she says, “Clearly as important providers of information, the media are more likely to promote better economic performance when they are more likely to satisfy three conditions: the media are independent, provide good-quality information, and have a broad reach.”

Obviously, these indirect influences are somewhat imponderable and difficult to quantify. Nonetheless, they should be considered when one tries to understand how the media can boost an economy.

But, as Islam points out, for the media to exert this kind of positive influence, there must be press freedom. The media must be unfettered by economic dependencies that lead to distorting the news. They must have the strength and independence to tell the truth.

Media as Economic Brokers

There is a less obvious, but more strategic role that the media have in promoting real economic growth. It is in bringing together buyers and sellers. This is done through the advertising content of media offerings.

In the simplest of economic settings, the physical marketplace is the venue for buyers and sellers to meet. It is a place where sellers put their wares on display, and where buyers know to visit when they have a need to buy something. But when a society’s needs for diverse products and services out step the capabilities of such a primitive marketplace, the role of the media comes into focus.

The media also can do much to stimulate a desire to buy. In a physical marketplace, that can happen only once a consumer has already ventured into the marketplace. If a consumer has gone to the marketplace to buy potatoes, and while there, sees some attractive tomatoes, that consumer may buy the tomatoes, too, even though that purchase was not initially intended. Much in the same way, the media can stimulate a desire to buy — but with consumers who have not even ventured outside of their homes.

How powerful an economic force media can be was demonstrated to me early in my career as a business consultant to media organizations. A new client came to me who was publishing a small quarterly magazine in a specialized construction field. This was a field of business that was suffering from negative growth. My client was looking for ways to cut costs in order to stay in business.

According to my analysis of this situation, however, the client’s problem was not that he was spending too much. It was that he was earning too little. So, I counseled him on how to improve his magazine and how to do a more effective job of selling its advertising space. This plan worked, and in no time at all, this unprofitable little publishing company had become profitable and was growing.

That’s not the point of this story, though. Something else started to happen. The industry that was served by this magazine turned around, too. Indeed, it started to grow. What caused the turnabout? The magazine had made itself relevant to the buyers and sellers of the field. It inspired their hope and confi- dence in the industry. And that in turn inspired its economic growth. As the demand for advertising space increased, the frequency of the magazine went from quarterly to bimonthly. For some years, now, it has been published monthly, each issue filled with lots of advertising. And the publisher has also become the successful sponsor of two annual trade shows.

An industry that was in decline was now brimming with prosperity. What had made the difference? What had the industry been lacking when it was in decline? It was in need of a modern marketplace, a place to bring together buyers and sellers, a place to inspire positive expectation. When this missing link was provided, the positive forces of a marketplace were unleashed, and economic growth ensued.

For the mass media, this kind of economic role is not limited to a single industry or segment of the economy. The mass media are positioned to serve a nation’s economy as a whole, to bring together buyers and sellers, and to inspire the kind confidence that leads to economic growth and development.

Multiplying Money

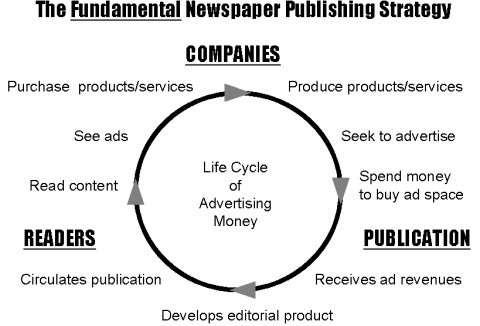

A good media outlet is actually like a money-multiplying machine for its

advertisers. Figure 1 illustrates how this strategy functions in a

newspaper.

Figure 1 — This diagram illustrates the flow of advertising money

through a legitimate publishing operation.

It shows that when

a company in an economy produces a product or service, it seeks to

advertise in order to find customers. In doing so, the company spends

money to buy advertising space. The newspaper receives this money, along

with advertising revenues from other advertisers. That allows the

newspaper to develop the publication’s content, an editorial product.

The publication is circulated to people who are interested in the content. As they read it, they also see the advertisements. In turn, they purchase the products and services that are advertised. In all, an advertiser spending 1000 rubles on advertising may get back 4000 rubles in business.

This All Means…

—The media can themselves constitute a vital segment of a country’s economy.

—They can intangibly encourage growth by promoting good governance and empowering citizens.

—They can be the brokers of commerce by bringing together buyers and sellers through advertising content.

—And, they can multiply the money of their advertisers.

Unfortunately, in Russia, these things are not generally happening.

Who Is to Blame?

There are a number of reasons why the growth of Russia’s media sector has been stunted.

One significant cause has been a government policy that discouraged advertising.

In most of the developed world, advertising is considered a legitimate activity of business. But, until recently, Russian law did not fully recognize a company’s advertising expenditures as normal business expenses. Only a very small amount of advertising was allowed as a tax deduction. That meant that advertising expenditures over that amount (equal to about 2 percent of a business’s turnover) had to come out of profits. It was not tax deductible. This policy placed quite a serious disincentive on advertising.

With a policy like that, is there any wonder why Russia’s advertising expenditures are such a small percentage of GDP?

Fortunately, as of July 2002, advertising in Russia has become fully tax deductible. This change will for the first time enable the advertising market to develop more normally. In turn, this should lead to greater development of the media as a sector of the economy, as more money begins being spent on media advertising.

Aren’t the Media to Blame, Too

While the media’s contributions to economic growth were constrained by the government’s disincentive toward advertising, that was not the only factor. The media themselves have obstructed economic growth.

The major way in which they have done this is by wasting the money that companies have spent on advertising. How did they waste the advertisers’ money? They did it by accepting payments from advertisers, and using that money to expose the advertisements largely to people who have no ability to buy the products or services that are advertised.

Today in Russia, outside of Moscow and St. Petersburg, only about 25 percent of the population have disposable income. These people have the capability of becoming good customers of the advertisers. But, the other 75 percent do not. So, when, for instance, a newspaper sells copies to this 75-percent segment of society, they are cheating their advertisers.

Many of the advertisers are unsophisticated enough to not realize that they are being cheated. Others understand the problem. But, there is nothing they can do about it. Most media outlets persist at exposing advertising messages to consumers without economic means. Advertisers have nothing but bad choices regarding where to spend their advertising money.

That’s not all, though. Media outlets cheat advertisers in another way, too. They fail to present the advertisements to consumers within a context of trustworthiness. That is because the media outlets are themselves not believed.

Why aren’t news outlets believed? It is because most news offerings are replete with stories that appear not because they are newsworthy, but because they were paid for. Think about it. The editorial role of a news staff is to sort through hundreds or thousands of events, to judge which of these events are of importance, and to present these stories to the consumers of the news outlet. The consumers, in effect, put the editorial staff in a position of trust to perform that function. When the media outlets offer paid propaganda masquerading as news, a violation of that trust occurs.

Illustrating the Point

A good illustration of this principle occurred two years ago in an experiment conducted by the International Center for Journalists. It convened focus groups in ten cities around Georgia (Gruzia). In each city, researchers asked participants to list what content or characteristics of a newspaper they want the most. Afterwards, each group was given stacks of newspapers, scissors, and glue pots. They were asked to cut out articles from all the local and national newspapers on hand, and from them, piece together their “ideal” newspaper.

The researchers then analyzed the content of the “ideal” newspapers and compared it with the wish lists. High on those lists were investigative reporting, coverage of government activities, and coverage of corruption. But the comparison between the “ideal” newspapers and the wish lists revealed a huge discrepancy. The things the participants said they wanted in a newspaper weren’t present in the “ideal” newspapers.

When interviewers confronted the groups with this puzzling outcome, the group members offered a nearunanimous explanation: “They didn’t clip any such articles because the ones in the existing newspapers were not believable or trustworthy.” The Georgians believed that these kinds of articles are almost always commissioned or sponsored by someone for political purposes, and that they are unfair and factually inaccurate.

The consumers went on to say what they want, and are acutely aware that they aren’t getting, are “news stories they can trust and believe.” What’s more, they said even though the economy is bad, “the reason they don’t buy more newspapers isn’t that they can’t afford to — but is that they don’t see anything in most newspapers worth spending money on.”

In Georgia, as in Russia, the media outlets have earned for themselves a reputation for not being honest. Either the articles are not factually accurate, or the editors have not been honest in presenting consumers with that which is newsworthy.

Given that reputation, what is the impact of this upon the advertisers? To understand that, think for a moment, that you are a shop owner. You want to hire someone to walk around town and tell people about your shop, that you have good products being sold at reasonable prices.

Two men have applied for the job. One, Igor, is known for being untruthful. When people see him walk down the street, they say, “there goes Igor the liar.” The other man, Ivan, is a former teacher. People respect him and appreciate that he has played a helpful role in the community. On one hand Igor will walk around town and tell people whatever you want, whether it is truthful or not. On the other hand, Ivan will tell only things about your business which are truthful. Who should you hire?

In this simple example, it is easy to see that hiring Igor would be of little value. He has no credibility. But, yet, media outlets are in actuality playing the role of Igor. From their own actions, they have established a dishonorable reputation for themselves. As a result, they have minimized their value as the couriers of advertisements.

What Prompted the Media to Do This?

Why have the media cast themselves in such a disreputable role? Haven’t they realized how self-defeating this has been?

Actually, the media are not themselves at the root of this problem. The government has been. Regulations have restricted the amount of advertising content that a media outlet can carry. This was not imposed as an absolute prohibition. Instead, tax policy was again used as a control. For instance, newspapers that contained more than 40 percent advertising content would lose exemptions from profits tax and VAT.

In the West, newspapers average 58 percent advertising content. It is practically impossible for a newspaper to be profitable, given a 40 percent advertising limit. Thus, the limit on advertising content has been, in effect, a government mandate for unprofitability.

Given that situation, how have newspapers survived? How have they managed to stay in business? To make up for their losses, they have become paid propagandists for “sponsors” consisting of government officials and business concerns. They take money in exchange for distorting the news or for presenting paid propaganda (hidden advertisements or zakazukha) as if it were news. Often these arrangements are disguised as investment transactions or as ownership. Whatever the form, the resulting arrangement establishes a financial dependency on the part of the media outlet with some entity that wants to distort either the news itself or the editorial judgment of the news editor.

It is the prevalence of this system that has led media outlets to earn for themselves the reputation of being dishonest. Remarkably, the system is also to blame for the problem described earlier, the dissemination of advertisements to those without the financial capability to buy what is advertised. You see, these “sponsors” want to influence society broadly. They want to reach voters not buyers. Thus, they encourage the media outlets that they sponsor to acquire the largest possible audience, irrespective of whether the people are legitimate targets for the advertisers.

It is perhaps ironic that the methods used by the sponsors and hidden advertisers are relatively ineffectual ways of influencing consumers. Almost all of the factors that research has shown to contribute to the success of an advertisement are not present. For example, “repeat exposure” of an advertisement increases its effectiveness. How many times can a newspaper run a phony news story? The size of an advertisement is directly proportional to its effectiveness. But, with hidden advertising, consumers have no perception of size. After all, that’s why it is called “hidden.”

It’s the Government’s Fault

Thus, there has been a conspiracy of laws that has mandated the unprofitabilty of media outlets, and has sent them into the clutches of politicians, oligarchs, and others to make up for the losses. This has had several catastrophic impacts upon economic growth:

—civil society has been unable to develop normally since citizens have not had the benefit of unbiased information with which to make their political choices,

—the growth of the advertising market has been suppressed by tax policy,

—the development of the media sector has been constrained by the absence of a robust advertising market,

—the impact of advertising expenditures has been greatly diluted by the way in which media outlets aggregate audience and because the outlets have engendered consumer distrust, and,

—media outlets thus have been ineffectual in bringing together buyers and sellers, and in inspiring economic confidence.

Ending the Tragedy

How can an end be put to this tragedy? What can be done so that the media can assume their needed role in boosting economic development?

Some people believe that enacting laws to end government sponsorship, subsidies, or ownership in the media field is the key. But, while I am in sympathy with the objective of such sentiment, I disagree with its necessity. To me, the real key is in creating the conditions under which a media outlet can honestly serve the needs of its natural constituents: the consumers and the advertisers. Right now both constituent groups can choose only from among bad alternatives. If good media outlets were to appear, ones that would serve the interests of the consumers and advertisers, not those of sponsors, I believe that Russians would be smart enough to choose them over the sponsored, dishonest ones.

But, that means that it must be possible for media outlets to achieve profitability from circulation and advertising revenues. President Putin has acknowledged this mandate. In 2000, he said,

“The unprofitableness of a sizable number of the media enterprises has made them dependent upon the commercial and political interests of the masters and sponsors who prop them up financially. This relationship enables these bosses to use the mass media for settling accounts with rivals, sometimes even to convert it into an instrument of misinformation in their struggles with the authorities. Because of this, we must guarantee journalists genuine freedom, not just the pretense of freedom, by creating in this country the legal and economic conditions that are needed for civilized information businesses to exist.” But, what has he actually done about it? To date, two noteworthy steps have been taken. (1) As of July 2002 advertising expenditures finally were made fully tax deductible. (2) Months earlier, the profits tax exemption that was predicated upon the 40 percent advertising content limit was allowed to expire.

These were very important steps toward establishing press freedom in Russia, and toward creating the circumstances that will allow the media to play their role in boosting economic progress.

Regrettably, there are still a couple of remnants of the old mediahobbling policy that remain. Earlier this year, the Duma passed and the president signed an extension of the VAT partial exemption that is tied to limitations on advertising content. Before that happened, Deputy Media Minster Grigoriev told me that it would be allowed to expire. But, apparently, the administration was not willing to stand up to the parliament in this period leading to the next election season.

Another issue is the services of post offices in subscription campaigns and for newspaper delivery. Grigoriev told me that revising the conditions for the media’s use of postal services was being examined with a view toward change. Subsequently, I asked him to clarify whether in the future there would be a linkage to the 40 percent advertising content limit. But, he’s failed to respond to repeated requests for clarification. Perhaps, the administration is retreating on this issue, too.

There’s Another Obstacle

Even if the VAT and postal policies that seek to limit advertising content remain, in my opinion, they are not pivotal. The partial VAT exemption is a relatively minor issue. And, publishers would do well to divorce themselves from the second-rate services of the post office by creating their own systems for subscriber acquisition and newspaper delivery.

That means that there is now no real impediment to publishers carrying more than 40 percent advertising content. For the first time, they can achieve profitability without sponsorships or subsidies.

Nonetheless, there is still an obstacle.

It is the intransigence of many media companies to abandon the current, corrupt system of sponsorship and paid-for stories, and become legitimate servers of their consumers (readers, viewers, listeners) and their advertisers.

Indeed, inertia is on the side of things staying the same. The media companies feel comfortable with the current system. It has been a sustaining system for them. They know how it works. It provides a comfort that is hard to abandon in exchange for a new way of doing business, which, for them, is an unknown quantity.

Whenever I have pressed media managers to explain why they will not change, they offer excuses:

—A manager who accepts payment for hidden advertising insists that compared to Westerners, Russians respond better to text than to obvious advertising matter. Of course, that is factually unsubstantiated. To the contrary, there is every indication that Russians, when given an opportunity, respond normally to marketing approaches that had been anathema in the previous era.

—An editor defends running a front-page story heralding discounts that are being offered by a local department store. He asserts that knowledge of the discounts is a benefit for readers. In reality, that is a shallow rationalization for abandoning editorial judgment in exchange for a few thousand rubles.

—Still another media manager rationalizes running hidden advertising masquerading as news stories by explaining that such is what his advertisers want, and that he is simply responding to a market demand. But, what if that media manager advised his advertisers about forms of advertising that would be more effectual? That might actually lead to the advertisers becoming more prosperous, and thus better customers for more advertising!

So, if inertia is on the side of things remaining the same, what is needed in order to instigate change? There must be a change in the business culture of the media sector, a new way for both media companies and advertisers alike to abandon current practices, and adopt truly market-oriented approaches to doing business.

Facilitating such a change in business culture is the target of the Russian Media Fund. It is a project that is backed by the International Center for Journalists (Washington) and the Media Research Center Sreda (Moscow).

RMF has developed a comprehensive program to instigate and nurture the transformation of the media’s business culture. Primary funding would come from Russia’s major consumer advertisers — companies that would receive direct financial gains from the fruits of the effort. The project’s presentations for seed funding have been received with interest from the Soros and Eurasia foundations. So far, however, neither has provided the needed funds. As this article is being written, the Russia Journal made an opening pledge toward this seed funding. Hopefully, other donors will join force in the near future.

It is Time for a Change

For the Russian media, all these circumstances present an unfolding of a new concept that has vast potential to improve the media landscape dramatically. It is a vision for a media that posses the strength and independence to tell the truth, a determination to serve the needs of the consumers and advertisers, and a franchise for promoting economic growth generally.

Heretofore, this vision could exist only in fantasy. Tax and advertising regulations had made it virtually impossible for media companies to even support themselves independently. That threw them into dependency upon financial overlords who compensated the media for their losses in exchange for the opportunity to color the news.

Recent regulatory changes have ended that mandate for subservience. But, this turn of events does not yet represent a turning point for the Russian media. Inertia is on the side of perpetuating the corrupt business practices that have been the media’s lifeblood.

The recent regulatory changes have, however, created a crucible, a place in which forces can interact to forge a fundamental change for the better. If the crucible is used wisely, if the media will reform their own business culture positively, then history will record these times as a proud, new beginning for the Russian media — and as a significant milestone in the development of Russia’s economy!

William Dunkerley is a business consultant to media companies internationally (wd [at]publishinghelp [dot] com), based in New Britain, Connecticut, USA. He has worked extensively in Russia and in six other post-communist countries.